Many

churchgoers, especially Lutherans it seems, often poke fun at themselves about

sitting in the same spot in the same pew over and over again. Of course, I

suppose I can’t throw too many stones in this regard, considering I get the

benefit of the same seat week after week. The fact yet remains: we can get a little

set in our ways, and even a little territorial, and woe to the unwitting guest who

“bumps” us out of our regular seat!

There

was a legend in the first congregation I served about one woman in particular who

liked to sit every week in the very back pew, in the seat right next to the

aisle. When one former pastor supposedly tried to rope off the back third of

the nave one particular poorly-attended Sunday so that everyone would sit

closer together and closer to the front, this one woman simply got up and left.

She wasn’t going to worship unless she could sit in her preferred seat. I ended

up getting to know Florence pretty well and she was super nice, but I was too

afraid to ever rope off her seat to see what she’d do. That’s an extreme case,

perhaps, but we all know what I’m talking about. We can laugh about it because

there’s an element of truth to it.

However,

as much as no one person really belongs in any particular pew here, I have to

admit I was touched this week when I heard one member her talk about her “pew

buddies.” I had gone to visit her in the hospital. As we were talking she

mentioned to me that the people who sat around her on Sunday mornings had known

about the upcoming procedure She then named them—one by one, the people who sit

around her each week—and the individual ways they offered care to her during

her rehabilitation. Now, her place in that pew is not “hers” by some right, as

if no one else could sit there, but it hers in the sense that it identifies her

place within the community. It gives her a space, a roll, a part in the bigger

scheme of things.

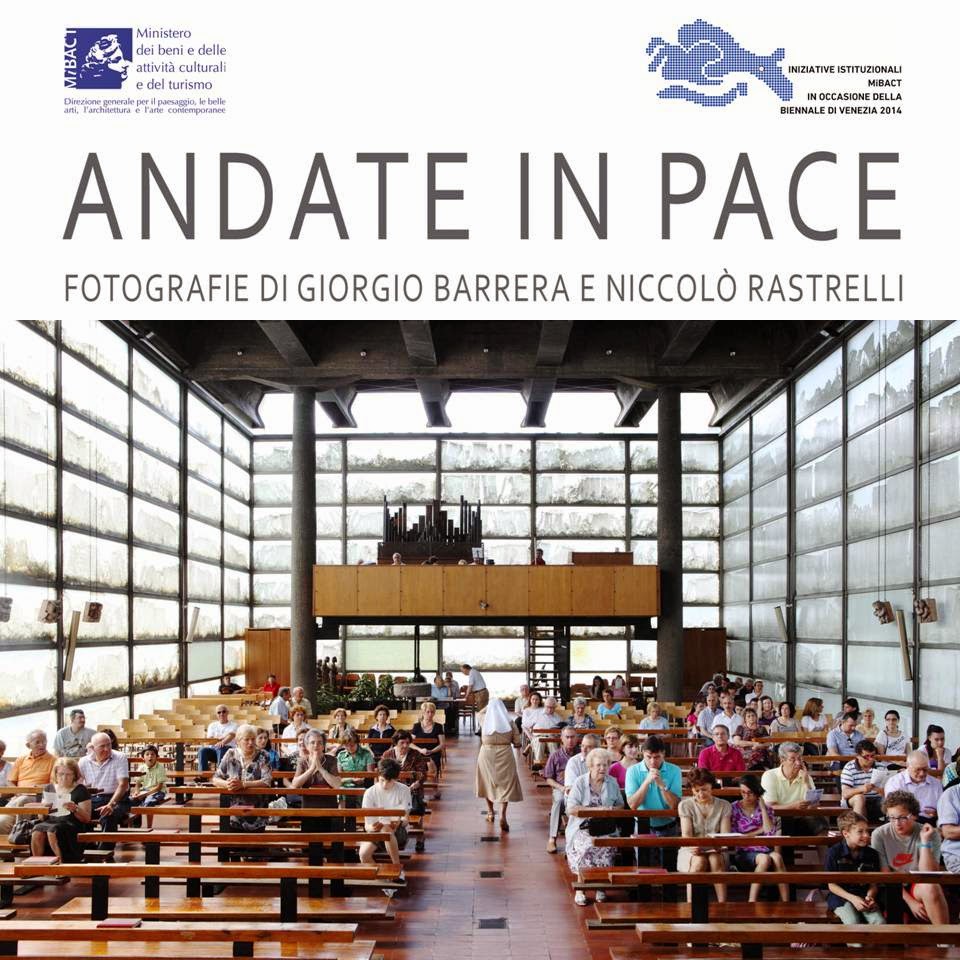

Two

Italian photographers recently published a book of photos using a camera set up

unobtrusively in front of the altar in several different congregations. It was

meant to give people and idea of what worshippers look like as a body as they

go through the motions of worship from the priest’s point of view. Most people

never get to see that perspective, but, as you can see in the book, clearly

each person has their place. The book is titled Go in Peace.

In

a world that is shifting so quickly, that gropes for peace, there is a lot to

be said for knowing our place, having a designated role, identifying where we

belong, understanding where we fit in relation

to the larger community, and, for some of us, becoming attached to a particular

pew on a Sunday morning is just one example of that. It certainly isn’t or

shouldn’t be the case for everyone. Nevertheless, what about you? Do you feel

like you have a place—a roll, a spot—in this community, or in any community, for

that matter?

For

the people of God, the reading and re-telling of Jesus’ suffering and death is

ultimately about finding our spot. This is perhaps the principal reason why,

every year—and on a much smaller scale, every week as the pastor lifts the

bread and the cup in Christ’s holy meal—we gather in churches and cathedrals

and worshiping communities around the globe and hear again the story of Jesus’

last days in Jerusalem. We read and listen to hear again where it is we fit in,

which role we might be playing in this great and tragic epic of God.

Pastor

and writer Kazimierz Bem writes in a recent article about worship: “Some things

are bigger than us. There needs to be a place where we are told uncomfortable

truths about ourselves, our world and even about God—where we ask the questions

our pop culture ignores or caricatures, and where we can look for answers. Where

we pause — and reflect theologically.”[1]

In

fact, one of the first acts of devotion that early Christians undertook was to

retrace Jesus’ footsteps in Jerusalem leading up to his crucifixion. Just as

the crowds once gathered to acclaim him as king and then later paraded him to

the hill of crucifixion, early people of the faith gathered annually in

Jerusalem to retrace his steps…but also theirs. They took palm branches and

walked along the city streets. They gathered for special celebrations of the

Lord’s Supper and kept vigil in darkened sanctuaries on Good Friday.

|

| "The Denial of Peter" (Simon Bening, 1525) |

But

none of this was done purely for the drama. It was done out of a need to

remember where they stood, where they sat, so to speak, as God’s wayward

people, as these events unfolded. They grasped, as we do, that this story was

not just something they listened to. It was something they participated in. It

is not just a chain of events that make us imagine things about God and the

world. It is a chain of events containing links that join us right to it.

So

it is, we pause again today not simply in this sanctuary but in the midst of

this story that is bigger than we are. We are confronted with uncomfortable

truths and, whether we admit it, we find ourselves asking difficult questions, often

prompted by different personal perspectives from the story itself. If they love

him, why don’t Jesus’ followers do more to stop this from happening, like get

him out of Jerusalem? Do I so quickly deny my relationship with the Lord the

way Peter does? For what reasons is releasing convicted murderer Barabbas the

better option? Deep down are we still more convinced of the power of violence

over the hard way of peacefulness? Do I, like Pilate, feel pressure from

society—from friends or culture in general—to take a stance about Jesus, but

end up noncommittal? And then clincher: if Jesus really has the forces of God

at his disposal, why on earth doesn’t he find a different way to bring about

his kingdom? This whole ordeal with the cross and the nails is ridiculous, in

the truest sense of the word. It’s like we find ourselves asking, along with

the mockers, “He saved others; let him save himself, if he is the Christ of

God!”

Yes,

before we know it, the story has done exactly what it set out to do: put us in

our place, whether we like it or not. We know that when we hear it we have a

place in this great and tragic—but ultimately triumphant—story of God.

|

| "Crucifixion" (Guilio Carponi, 1648) |

So,

today, I invite you to glance around at your “pew buddies,” your fellow members

of a broken world, and speak up with boldness and claim a part. There’s a place

for you in there somewhere. Maybe you’re like Florence and know exactly where

you belong. But remember: just as we take in the despair of this part of the

story, I assure you we will take part in the hope to which it leads, a

permanent place at the table of mercy…from God’s view, one congregation, one

people, faces all lifted up toward the risen Lord.

Thanks

be to God!

|

| Andate in Pace ("Go in Peace") |

The Reverend Phillip W.

Martin, Jr.