“How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of the

messenger who announces peace, who brings good news!”

On the

weeks leading up to Christmas we love

the sound of the doorbell at our house. It

doesn’t get rung too often during the rest of the year, but these days it’s

more common, and the chime of the

bell means one thing: the UPS

delivery man has done it again. A

messenger who brings good news: there

is a package—or maybe more!—on our front step. No matter how quick we are to respond, the delivery man is usually already off the porch before we arrive

at the door. We catch a glimpse of

him scurrying back to his vehicle, bounding into the driver’s seat, on to the

next stop, on to the next doorbell. In his wake, our excitement is just

beginning. We bring them in, squirrel

them away in secret, and wait for the

proper time to wrap and then open them. The

doorbell is kind of a fun by-product to on-line shopping.

And what a

job: to deliver the presents, to deliver

the news! Of course, if you are

receiving a package from the Martin family this year, that doorbell will be ringing after Christmas since we were kind of behind the eight ball in that department

lately. And with Christmas cards. But I digress. In any case, it will be a glad sound, and those are beautiful, parcel post feet.

The

Epiphany Youth group spent some time this week as those “beautiful feet” on the

front porches of several of our homebound members. The youth were not

delivering any packages, per se, but

they were delivering good news. They went, you see, to sing Christmas carols to

them, and, so long as the Holy Spirit made it possible, to spread a bit of the

cheer of that good news of Jesus’ birth. It was a wonderful evening. The

weather cooperated nicely, and our caravan of about 10 vehicles managed to make

it to three members’ homes before we had to come back here for supper. We

learned, among other things, that not everyone knows all the words to “What

Child is This?” by heart, but we managed to mutter through on the strength of a

few clear voices. We also learned that they’d like us back more often. One gentleman,

confined to his house by advanced Parkinsons’, stuck out a wavering arm and invited

us to come again next week.

Singing

Christmas carols to the homebound is actually something my own church youth

group did when I was a kid. It was a yearly thing. We’d spend one night right before

Christmas making the rounds, visiting different homes and assisted living

facilities with our rusty-voiced Christmas cheer. Occasionally the person to

whom we were caroling, although frail, would be able to make it to the door and

join along in the singing. Sometimes, if it was too cold, they’d stand behind

the window and peer out at us, our faces barely lit by the glow of the small

candles we held in our hands. We never actually went in anyone’s house,

however. It would have been too crowded, too much of an imposition.

One year,

however, our pastor took us to sing at the home of Bob Snow, an elderly member

who was in the final stages of cancer. And by “final” I mean the last few days.

He was bedridden, already on a respirator or oxygen or some other apparatus to

aid his breathing. An unused bedpan or two were stacked up on his nightstand. There

was no other way to sing to Bob than by standing in his bed room. By his bed. Where

he was dying. And so we all traipsed in there, well past the front porch, through

the family room, and encircled his bed. The only lights in the room were

provided by our candles.

The last

we’d seen Mr. Snow in church was months before, and he looked much different

now. He was wan and skeleton-like. His weak face, which was as white as his

name, was already sunken in from the toll of the disease, and the whole scene

made me, a middle-schooler, feel downright uncomfortable. I was barely at ease

in my own skin in those days, and I didn’t know how to look at his. I remember

elbowing my way back from the front row. “Why did his wife bring us in here?” I

thought. “Surely he could have heard us from outside.” And there, in that room,

as the breathing apparatus gurgled and hissed, we sang Christmas carols at

death. We lifted up our candles, whose glimmer now reflected off the wet cheeks

of his family members, and sang these happy songs—these songs of good news about

someone’s birth—to some who was obviously dying.

Hark the Herald Angels Sing, glory to the newborn

King!...Joy to the World! The Lord is come!...Silent Night! Holy Night! All is calm, all is…bright? Indeed,

although maybe not in the way I could recognize. “How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of the

messenger of those who announces peace, who brings good news, who announces

salvation, who says to Zion, ‘Your God reigns!’”

At that time, in those teenager days of robust health

and raging hormones, it didn’t make

much sense why we would do something like that, why we would make some of us so uncomfortable at such a joyous time of the year, why we would pull back the curtain that hid the dying from our light and think on such sad things.

To sing songs of a birth while someone was dying? What kind of a cruel, insensitive endeavor is this?

But

they—the wife, the sons, the pastor, and Mr. Snow, no doubt—were thinking about

this: “And the Word became flesh and lived

among us.” The good news that we were announcing—the good news that we have

brought to us this great morning—is not simply that Jesus is born, but that

Jesus is born to die. And if, as the prophet Isaiah says, our God reigns at

all, it is because God has reigned in places like Bob Snow’s bedroom the week

before he died. When we say that the

Word of God became flesh and dwelt among us, we mean that he lived the full

extent of the human experience. He suffered what flesh suffers when it

encounters the brokenness of creation. He endures what our flesh endures as it

lives in a world prone to danger and disease. God has miraculously been wrapped

in our skin, as wan and weak and pale as it can sometimes be. When we hear that

God’s Word—God’s very essence and very happening—became

flesh and lived among us, then we hear the length that God is willing to go bear

his arm and make us his forever. We hear

of the lengths God will go to restore human dignity. And that is precisely what Mr. Snow would

need to hear. As it turns out, maybe it

is those lesser-known words of “What Child is This?” that say it best, and that

bear being taken to heart:

“Nails, spear

shall pierce him through

The cross be

borne for me, for you.

Hail, hail

the Word made flesh,

the babe, the

Son of Mary.”

Earlier this week, as my family sat

down to eat our dinner, our five-year-old daughter requested to say the

blessing. She said thanks for the food, but before she said “amen,” she

inserted a final petition with the most serious inflection: “And God,” she

said, “help us remember that we can’t open our presents until Christmas. Lord,

Have mercy. Hear our prayer.”

Well, it’s Christmas! No time for holding back! Ring

the doorbell and rip open the gift, the gift of Jesus. Tell the good news…on

the porch, at the table, at the bedside, in the tomb: Salvation has come. Our

God reigns!

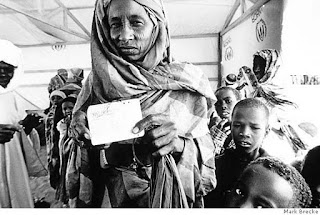

| Orthodox icons of the Nativity of Jesus often depict his birthplace as a cave, evoking his place of burial. |

Merry

Christmas!

The Reverend Phillip W. Martin, Jr.